Description

The Barnes Review

A JOURNAL OF POLITICALLY INCORRECT HISTORY

MAY/JUNE 2018 ❖ VOLUME XXIV ❖ NUMBER 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

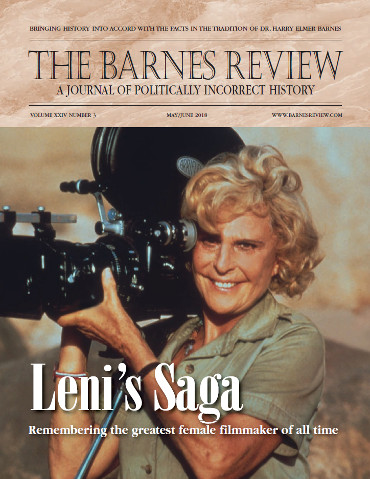

LENI RIEFENSTAHL’S SAGA

BY JOHN WEAR, J.D. Leni Riefenstahl made her mark with the documentary “Olympiad” about the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin and her National Socialist propaganda films. Starting out as a dancer, she literally “broke a leg” to become a movie star and then the most important film director in Nazi Germany. Is she the greatest female film director of all time?

NIXON & TRUMP VERSUS THE LEFT

BY DR. MATTHEW RAPHAEL JOHNSON. In the private view of the mass media, we live in a media-cracy. The people may elect a president, but if the Big Media do not like him they try to overthrow him. Richard Nixon and Donald Trump are two such. One promised to “clean house”; the other has sworn he will “drain the swamp.

THE ASSASSINATION OF THE MAN WHO KILLED JESSE JAMES

BY CLINT LACY. You may not have heard of Edward Capehart O’Kelley, but he is the man who shot the man who is said to have shot Jesse James, the famous outlaw. Here is his saga.

THE CRUCIFIXION OF CHRISTIANITY

BY MICHAEL WALSH. Beginning in 1917, the real holocaust unfolded, not in Germany but in Russia, and not of Jews but of Christians by communists. Establishment outlets tell us Jews are “wrongfully accused” of inflicting bloody Bolshevism on the world. Who is correct? You decide.

THE LEGACY OF SALVADOR BORREGO: THE MEXICAN REVISIONIST

BY MARGARET HUFFSTICKLER. Salvador Borrego will always be remembered as a titan of Revisionist history. While critical of the Jewish global elite, he noted that this did not make him anti-Jewish, any more than criticizing the Mexican government makes one anti-Mexican.

50 YEARS LATER: WHO KILLED MLK?

BY PAT SHANNAN. Was civil rights leader Martin Luther King killed by James Earl Ray, lone nut and smalltime white-collar common crook? Or was it a government operation? Overwhelming evidence points to a Deep State hit. Will justice ever be served in this assassination?

SECESSION & THE LAW OF GOD

BY PASTOR EDWARD DEVRIES. Is the United States “one nation, under God, indivisible,” as we have been trained to parrot? Was it ever? Why did ancient Israel of the Bible split in two? The Old Testament of the Bible is a gold mine of evidence that secession is a God-given right.

50 YEARS LATER: WHO KILLED RFK?

BY PAT SHANNAN. You have been told Sen. Robert F. Kennedy was murdered 50 years ago by a Palestinian named Sirhan Sirhan. But the shooting is obviously an extension of the JFK assassination five years earlier. Both killings were coups d’état— the RFK one eliminating the man who was sure to be elected president in 1968.

HERBERT HOOVER RECONSIDERED

BY S.T. PATRICK. He left office a virtual pariah. But was the much-maligned Herbert Hoover an unsung hero? He is consistently ranked at the bottom of a list of America’s “best presidents.” But is this all just unceasing pro-FDR propaganda from the leftist press and academia? Hoover, it turns out, was an extraordinary man.

WORLD WAR I SECRETS REVEALED

BY MARK ROLAND. A constitution for the Germans would be nice, thought the Allies in 1949. The Soviets were now the largest threat to the West, and a transition from military occupation to self-governance was needed in Germany. But few know about the secret agreement arranged the night before the constitution was signed—May 23, 1949—sealing Germany’s fate until 2099.