By Dr. Ed DeVries

In 1905 sporting goods entrepreneur Albert Spalding organized a group that he called the Mills Commission and tasked it to determine the origins of the game of baseball. Their conclusion was that Union General Abner Doubleday, who had died 12 years prior, was the game’s inventor. This was based mainly on the testimony of one man, a 71-year-old miner from Denver named Abner Graves.

In 1905 sporting goods entrepreneur Albert Spalding organized a group that he called the Mills Commission and tasked it to determine the origins of the game of baseball. Their conclusion was that Union General Abner Doubleday, who had died 12 years prior, was the game’s inventor. This was based mainly on the testimony of one man, a 71-year-old miner from Denver named Abner Graves.

Graves claimed to have witnessed the actual formation of the game that he claimed Doubleday called “base ball” at a field in Cooperstown, New York in 1839. He further claimed that Doubleday’s game was an improvement of a game called “town ball,” being played by students in Cooperstown.

Doubleday was born in New York in 1818. In 1839, he was a student at the United States Military Academy, also in the state of New York. Based on those two collaborating facts, it would not have been impossible for Abner Doubleday to have invented the game of baseball.

Their evidence was tenuous, at best. Other facts would have to be ignored, such as the fact that West Point has no record of his leaving the United States Military Academy for Cooperstown at any point in 1839, the fact that there were no letters or personal accounts from Doubleday making any mention of the game of baseball, or that no evidence exists that Doubleday had ever made any claim in writing or in conversation that he was the man who designed the first field or created the first set of rules.

Still, the Mills Commission had stumbled upon a convenient and compelling story to describe the game’s origins in patriotic terms: invented by an “American hero,” who had graduated from West Point, rose to the rank of Major General, the veteran of two wars etc. The game’s place of origin would be in a small rural town, without the help of any foreign or industrial interest. A pastoral game, made in the USA, that became the nation’s pastime. Certainly, that was a lot better than ascribing the game to British origins?

THE LEGEND OF ABNER DOUBLEDAY

The truth is that General Doubleday does not need to be credited with the invention of baseball in order to be a person of legend. He was, after all, credited with firing the first shot against the rebellion in the War Between the States.

On April 12, 1861 South Carolina troops opened fire on Fort Sumter. In response, Doubleday divided his company into three details to return fire. The first shot was reportedly fired by Abner Doubleday himself.

This shot was not very impressive. It bounced off of the sloped roof causing no damage. But after several more shots he and his men were able to eventually silence the rebel gun.

Doubleday would also lead troops into heavy fighting at Second Mannassas, South Mountain, Antietam and Gettysburg. He was at the Battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville although his unit saw limited action at Fredericksburg and did not participate at all at Chancellorsville having been ordered to the back line of the battle.

After the Battle of Gettysburg he was promoted and ordered to Washington, D.C. where he was put in charge of the Capitol City’s defenses after Jubal Early threatened to attack.

Abner Doubleday was not a great military commander. But he wasn’t a bad one, either. His actions at Fort Sumter and Gettysburg were almost “legendary.” But for whatever reasons, those legends, birthed by Doubleday himself, would fail to endure. The myth that he invented baseball stuck. And over a century after the Mills Commission, The Baseball Hall of Fame, established in 1936, is still located in Cooperstown, New York in honor of Abner Doubleday.

THE EARLY HISTORY OF BASEBALL

The fact that our nation’s pastime has origins in the games of a foreign country makes no difference at all. It is still a great American game that was enjoyed as much, if not more, by “Billy Yank” and “Johnny Reb” during the War Between the States, as it is by millions both North and South today.

While it is difficult to pinpoint the origins of modern-day baseball to one specific moment, or to one specific man, or even to one other sport from which it could have been derived, the game is obviously a variation of at least a few different British games, namely cricket, rounders, and “stool ball.” It also appears to be inspired by the early American games called “cat-ball” and “town ball.”

On September 23, 1845, a New Yorker by the name of Alexander Cartwright was credited with publishing the “20 Original Rules of Baseball.” These rules later came to be known as the Knickerbocker Rules, named after Cartwright’s New York Knickerbocker team. The first recorded game played under the Knickerbocker Rules was scored on June 19, 1846.

BASEBALL DURING THE WAR BETWEEN THE STATES

In the next 15 years, leading up to the War Between the States, the game would become popular in both the Northern and Southern areas of the country. The War was most likely the catalyst that cemented the game into our national soul.

The movements of soldiers over great distances and the exchange of prisoners helped further standardize the game’s rules and style of play among men from a variety of locations and cultural backgrounds. The games provided soldiers with a means of escape from the hardships of war. Baseball, especially when teams of “Yanks” and “Rebs” played against each other, developed a kinship between men who otherwise were enemies. The importance of teamwork was accentuated. The games resulted in boosts in morale. By doing so, a foundation was planted for baseball to become the eventually reunited nation’s pastime.

Even Abraham Lincoln was a baseball fan, ordering a diamond to be constructed on the lawn of the Executive Mansion. He would regularly skip cabinet meetings to play with soldiers and children. His friend, J.H. Littlefield, would recall: “As a relaxation from professional cares he would go out and play ball… . I have seen Mr. Lincoln go into this sport with a great deal of zest.” His son would write that: “We boys hailed [Lincoln’s] coming with delight because he would always join us on the lawn. … I remember vividly how he ran, how long were his strides, how his coattails stuck out behind.”

Countless baseball games were organized in Army camps and prisons on both sides of the Mason Dixon Line. However, little documentation exists on these games, as scorebooks, as we know them, were not yet kept, and most of the information we have about them has come from letters written by both officers and enlisted men to their families on the home front.

A private in the 10th Massachusetts wrote: “Ball-playing having become a mania in camp… Officer and men forget, for a time, the differences in rank and indulge in the invigorating sport with a schoolboy’s ardor.”

One of their opponents, a private from Virginia, would write: “It is astonishing how indifferent a person can become to danger. The report of musketry is heard but a very little distance from us . . . yet over there on the other side of the road most of our company, playing bat ball and perhaps in less than half an hour, they may be called to play a ball game of a more serious nature.”

One prisoner, Sgt. William J. Crossley from Rhode Island, records in his memoir that the “great game of baseball [offered] as much enjoyment to the Rebs as to the Yanks, for they came in hundreds to see the sport.” Of one game in particular, played between teams of prisoners who were previously held at Tuscaloosa and New Orleans, he writes, “I have seen more smiles today on their oblong faces than before since I came to Rebeldom, for they have been the most doleful looking set of men I ever saw, and the Confederate gray uniform really adds to their mournful appearance.”

There is at least one photo in the National Archives that clearly shows a baseball game being played. Several newspaper artists also depicted ballgames and other forms of recreation devised to help boost troop morale and maintain physical fitness. Regardless of the lack of “media coverage,” military historians have proved that baseball was a common ground in a country divided, and helped both Union and Confederate soldiers temporarily escape the horror of war.

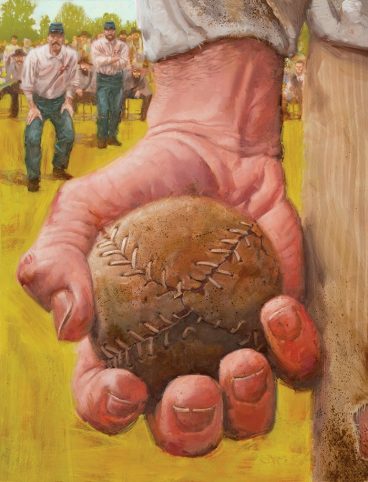

In the camps of both armies the commanders encouraged baseball games as a way to keep their men physically fit and mentally alert. Some soldiers, both Northern and Southern had actually taken baseball equipment to war with them. When the proper equipment was not available the soldiers often improvised with fence posts, barrel staves or tree branches for bats & yarn or rag-wrapped walnuts or lumps of cork for balls.

Perhaps the most notable War Between the States game was played in Hilton Head, South Carolina on Christmas Day in 1862. Over 40,000 troops watched and cheered the game as the hostility of war was suspended for the holiday.

Another notable game was enjoyed in North Carolina by both Union prisoners and their Confederate guards on July 4, 1862. In that day’s battle, neither side would wield deadly weapons, just bats and balls. The contest was a friendly one. Dr. Charles Carroll Gray, a Union prisoner at Salisbury, notes in his diary that the occasion is “celebrated with music, reading of the Declaration of Independence, and sack and foot races in the afternoon, and also a baseball game.”

Salisbury Prison was a regular venue for baseball. Early on, most every day except Sunday, the prisoners would form up teams and play. Always their guards would watch with interest. Eventually, the guards formed their own team and “Johnny Reb” and “Billy Yank” would play each other. The games provided amusement, exercise, diversion, even camaraderie among prisoners and guards alike.

In 1863, a game was played in Texas, only to be interrupted by an attack. According to Union solider George Putnam: “…the centerfielder was hit and was captured, left and right fielders managed to get back to our line. The attack was repelled without serious difficulty, but we had lost not only our centerfield, but the only baseball in Alexandria, Texas.”

Throughout 1863 the 24th Alabama records playing daily baseball games while awaiting the advancing Federal Army led by General William Tecumseh Sherman.

Throughout 1864, POWs from the 11th Mississippi staged a series of contests playing the guards at a Union Prison Camp in Sandusky, Ohio.

In 1865, following Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, soldiers from both sides played a series of baseball games. Was the first “World Series,” or at least the first national championship series, a contest between the Army of the Potomac “Invaders” and the Army of Northern Virginia “Defenders”? The “Invaders” won the war. But the “Defenders” went home with baseball’s first pennant.

When the War Between the States ended, men returned to their homes, North and South, to share their knowledge of the new game they had learned. Organized baseball grew in popularity and served as a means to unite a country that had been torn apart by the brutal five year conflict.

BLACKS AND BASEBALL

All-negro teams began to form in the 1840s in Manhattan and Brooklyn and then spread, during the 1850s across the nation so that when The War Between the States began there were dozens of all-negro ball clubs playing organized baseball from New York to New Orleans.

The start of the War disrupted ball playing by both whites and blacks, but 1862 brought a baseball revival. And while Northern military units were segregated, Confederate units were not. This meant that amongst Southerners, whites and blacks played baseball together, on the same teams. But amongst Northerners, the teams were segregated. And often Northern teams would not play Southern teams if the Southern team had any blacks on it. So it seems that the Jackie Robinson story started long before Jackie Robinson. As many of you remember, in 1947, Jackie Robinson broke professional baseball’s “color barrier” when he started as a first-baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers. The next ten years of our nation’s history were very difficult because of it. Had the South won the War Between the States it is very possible that professional baseball would not have been a segregated sport. Even though Robinson was playing for a northern team, the Dodgers had just hired a new general manager, a Southerner from Missouri, Branch Rickey. It was Rickey who wanted to hire Robinson and the majority of the opposition for having a “colored” person playing in the Major Leagues was coming from Northern clubs, owners, and players, NOT from Southern clubs and fans, as was depicted in the movie “42.”

Newspaper reporters in the North used racist stereotypes to describe blacks playing baseball in the 1950s. They also did so during the War Between the States. On October 17, 1862 The Brooklyn Daily Eagle published a brief account of a match between an unknown Southern team and a team of Yankee soldiers. Its headline introduced the contest as: “A New Sensation in Baseball Circles – Sambo as a Ball-Player and Dinah as an Emulator.” The reporter observed that everyone in the large crowd was “as black as the ace of spades.”

By the end of the War, baseball had become one of the top entertainment attractions for black populations throughout the country. But the North won the war and “reconstruction” was imposed upon the South. Basically “reconstruction” was a 20-year military occupation of the South by the North. “Segregation” as we think of it, really began during reconstruction and was imposed upon Southerners by their Yankee occupiers. You guessed it, during reconstruction, the Yankees segregated baseball. It was already segregated in the North. They segregated it in the South too.

So the blacks formed their own “negro leagues” which grew in popularity despite great and numerous financial pressures. The Negro Southern League, the Negro American League, the Negro National League and numerous other leagues became a strong part of our nation’s culture, both Northern and Southern, and produced hundreds of the nation’s greatest baseball players.

BASEBALL CARDS – A “SOUTHERN INVENTION”

Baseball cards, a favorite of children of all ages, are usually, as we all know, purchased in packages with chewing gum. The first baseball cards however were sold by Southern tobacco companies and packaged with pouches of chewing tobacco.

AN ONGOING TRIBUTE

Most people consider the beginning of the War Between the States to have occurred on April 12, 1861, when the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. General Lee would surrender to General Grant at the McLean House in Appomattox, Virginia on April 9, 1865. The War began, and ended, in April. This is why 150 years after “the bloodiest war in our nation’s history,” Major League Baseball still maintained the tradition of holding its Opening Day ceremony in April – honoring both “Billy Yank,” and “Johnny Reb” for laying down their muskets and picking up a bat and a ball. By moving the openers to earlier dates in March, both last year and again this year, Commissioner Rob Manfred, maybe knowingly and perhaps unknowingly, has done a disservice to the great game, and to its great history.

- Visit www.dixieheritage.net for a free copy of Dr. Ed’s book The Truth About the Confederate Battle Flag.