By Dr. Edward DeVries

The second world war was a time of exponential growth in the technology of warfare. Rifles, pistols, rockets, tanks, jeeps, airplanes, ships and submarines were developed and redeveloped so as to make them capable of killing faster, more cheaply and in greater numbers than ever before.

The Axis powers of Germany and Japan both developed technology that, had they only had the capacity to mass produce it, would have not only changed the way in which war was waged, the world itself would have been changed. Remember that, after the war, it was former German scientists and engineers who developed the rocket and atomic technology of both the United States and the Soviet Union.

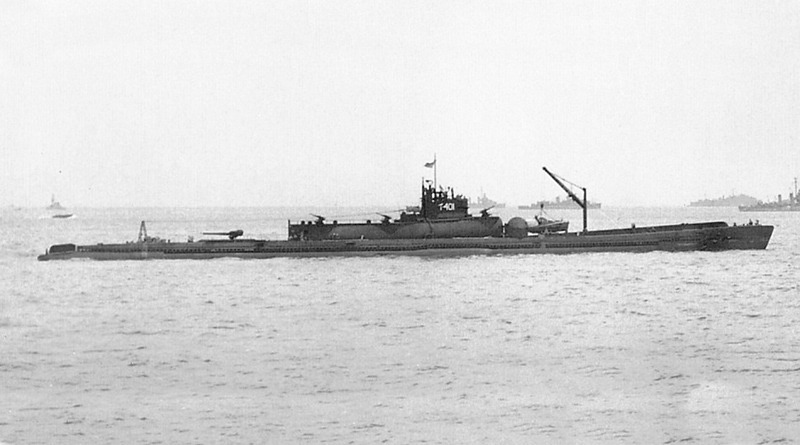

Perhaps the most interesting engineering accomplishment of World War II lies at a depth of almost 2,700 feet below the surface of the Pacific Ocean. It is the wreckage of the scuttled I-401, an underwater aircraft carrier built by the Imperial Japanese navy. In its day, it was the largest submarine that had ever been built. It retained that record until nuclear ballistic missile submarines were introduced in the 1960s.

The I-401 was one of three Sen Toku class Japanese submarines. Not only was it an underwater aircraft carrier, it could also travel around the globe one-and-a-half times without refueling. This made it capable of fueling in Japan, attacking the east coast of the United States and returning to Japan undetected—and without needing to stop and refuel. Had any of its planned missions been carried out, thousands of Americans could have died on U.S. soil from Los Angeles to New York City.

Soon after the successful Japanese attack of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto presented to his government a plan to attack the continental United States. A fleet of underwater aircraft carriers would surface in strategically determined locations all at once and bomb unprepared targets with brutal efficiency.

But the execution of the plan required something that simply did not exist: an underwater aircraft carrier. Adm. Yamamoto was paired with Capt. Kameto Kuroshima, an engineer and designer. Their brainchild would become the Sen Toku class of submarines, named I-400, I-401, and I-402 as they came off the assembly line in 1945.

Adm. Yamamoto’s plan had called for 18 Sen Toku submarines to launch an overwhelming attack on both the eastern and western seaboards of the United States at the same time. But even with the best engineers working around the clock, early Japanese war losses made the construction of such massive submarines nearly impossible.

Toward the end of the war, the Japanese managed to construct three of the 18 massive vessels. Each had a watertight aircraft hangar capable of housing three Aichi M6A aircraft.

With only two ships in service, Yamamoto could not launch the massive attack on the United States that he had originally envisioned, but he believed their combined power and payload more than capable of launching an attack that would have totally destroyed the Panama Canal. And he even positioned the ships to do it. Why the plan was abandoned at the last minute, no one knows. Had it succeeded, the Japanese would have effectively cut off the Allies’ most efficient supply route to the Pacific and added months or maybe even years to the war.

Perhaps the reason was that, by the time I-400 and I-401 had been put into service, the tide of the war had already turned against Japan and the resources the Japanese desperately needed for offensive plans were even more necessary for defending their holdings closer to home.

But, even with all other offensive naval plans abandoned, still one Japanese offensive plan remained in place. Scheduled for September 22, 1945, operation Cherry Blossoms at Night would have had I-400, I-401, I-402 and two more Sen Toku-class subs surface off the coast of San Diego. Their Aichi M6A airplanes would allegedly have dropped bombs of fleas infected with a biological agent that would have spread a plague throughout the U.S. On August 15, however, the plan was also abandoned when Emperor Hirohito announced the Japanese intention to surrender.

Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night actually called for five Sen Toku class submarines. The Japanese Navy believed that they could push at least one, maybe two more, the I-403 and I-404, through rapid production. Hence the reason why the plan’s execution date was pushed to September 22.

The underwater aircraft carriers, like any other military submarine, were equipped with torpedo tubes for underwater combat. But their gigantic size, coupled with the fact that they were built with the same size rudders used on regular submarines, handicapped the vessels with extremely poor maneuverability. Thus, their captains were loathe to engage enemy ships and did their best to avoid combat with other subs.

Also, because of their extreme length, the dive times of the I-400 and I-401 were more than twice that of a regular submarine. This left the unsubmerged subs vulnerable to air attacks for extended periods of time.

The Japanese actually foresaw these problems when they designed the behemoth submarines and, yet, they built them anyway, because Adm. Yamamoto and the emperor both believed that the disadvantages would be offset by the fact that these gigantic submarines could launch a powerful surprise air attack against the U.S. This air attack, they envisioned, would turn the tide of the war back in Japan’s favor and sow fear in the American citizenry, possibly diminishing public support for continuing the war against Japan.

But at war’s end, the vision was never realized, and none of the underwater aircraft carriers ever engaged an enemy vessel, launched an attack or saw any maritime combat.

Despite all of their intelligence, the Allies did not learn of the Sen Toku class submarines until after the Japanese surrender. It was then that the U.S. Navy took possession of all three of the underwater aircraft carriers along with 21 other Japanese submarines. I-400, I-401 and I-402, under American crews, were ordered to Sasebo Bay in Nagasaki Prefecture where they could be studied by the best engineers of England and the United States.

But by then, our “allies,” the Soviets, had also received reports of the underwater aircraft carriers and had dispatched their own agents to study them. To prevent the design of these potentially war-altering Japanese aircraft carrier/submarines from falling into Soviet hands, American naval leaders ordered them scuttled at sea. The three submarines were reportedly taken out to a spot somewhere southeast of the southernmost islands of Japan, packed with C4 explosives and sunk. But, secretly, I-401 and I-402 were sailed to Hawaii where U.S. Navy engineers inspected and blueprinted them. Shortly thereafter, they were sailed to an unknown location where they were torpedoed and sunk.

The exact locations of the scuttled submarines remained unknown until March 2005, when the wreckage of

I-401 was discovered by the Hawaiian Undersea Research Laboratory.

Many of the secrets of her design, however, will most likely forever remain with her at the bottom of the ocean.

This article appeared in the January/February 2021 issue of The Barnes Review. Click here for more information.