A Titanic Hero: Senator William Alden Smith

By Michael Collins Piper. Once again the saga of the ill-fated Titanic has captured the media’s imagination. Here’s some history that’s been virtually forgotten—the story of a populist law maker who never set foot on the ship yet became an un-sung hero of one of the most famous maritime disasters in history.

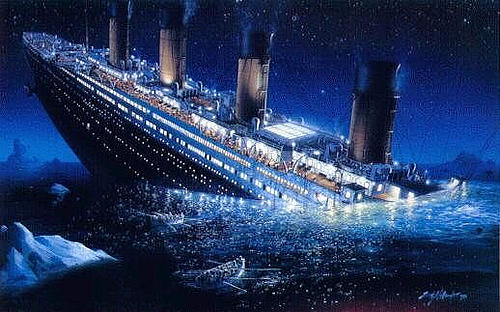

The liner RMS Titanic had barely sunk before legends began to surround the magnificent ship. At 11:40 p.m. on the night of April 14, 1912, the Belfast-constructed British White Star Liner, the newest, largest and most luxurious passenger ship in the world, bound for New York on its maiden voyage, struck an iceberg. After remaining afloat for slightly more than two hours, the Titanic—which one shipping journal of the time proclaimed “practically unsinkable”—foundered at 2:20 a.m. on the morning of April 15.

There were 705 survivors among the passengers and crew. The vast number of the survivors escaped in lifeboats many of which were launched less than half full. Only a handful of those who survived had remained on board the ship until it sank, later swimming to safety. Some 1,500 people died that cold April night.

In the aftermath, salvage vessels arriving on the scene recovered the bodies of several hundred of the victims—men, women and children many of them floating upright in their life preservers. They had not drowned, but had frozen to death in the icy waters of the North Atlantic. At that time, the loss of the Titanic was, by far, the world’s greatest recorded catastrophe at sea. In subsequent years there were greater losses of life in other sea tragedies, but none of them ever so captured the imagination of the public.

In the wake of the disaster many heroes were recognized, among those who perished as well as among the ship’s survivors. Their bravery on that historic night has become a part of popular history. There was, however, at least one Titanic survivor who emerged as a villain in the aftermath of the sinking. Members of the press were tough on J. Bruce Ismay—they called him J. “Brute” Ismay. He was the managing director of the White Star Line and general chairman of the White Star’s parent company, International Mercantile Marine.

As would be expected, Ismay had taken one of the plusher staterooms for the doomed vessel’s maiden, hopefully record-time-setting crossing. But as one of the last lifeboats was being lowered, he stepped in and was rescued. Although a number of other male survivors had escaped in lifeboats, Ismay was seen not as using common sense but rather as exhibiting craven cowardice. The White Star director was hounded relentlessly by the media. His mistake, it seemed, was having survived when so many others (particularly women and children) had died aboard the vessel, the flagship of his family’s shipping line. But then, as we shall see, there is much, much more to the story.

The recorded acts of heroism during the sinking and afterward have been the subject of countless books, thousands of newspaper and magazine articles, and several motion pictures (including two of recent vintage) as well as two Broadway productions.

Despite all this, few people—even those intimately familiar with the Titanic legend—remember the Titanic hero whose legacy in the aftermath of the sinking had a remarkable and historic impact above and beyond the dramatic events the night the magnificent liner went down: William Alden Smith.

Smith was neither a passenger nor a crew member aboard Titanic. Nor did he have anything to do with the dramatic early morning rescue of the survivors. At the time of the disaster Smith was sleeping comfortably in his home in Washington, D.C. He was the energetic populist Republican U.S. senator from Michigan who organized and chaired the Senate’s then-highly controversial and internationally-publicized investigation into the sinking of the Titanic.

Smith’s investigation of the calamity is all but forgotten, although it created a major media frenzy following the incident. Later, during the Watergate scandal, Smith’s inquiry received passing media mention: the 1970s hearings were being held in the same cavernous U.S. Senate chamber. In fact, Sen. Smith’s Titanic inquiry was an immense drama unto itself. It proved a momentous turning point affecting sea travel to this day.

Born in Dowagiac, Michigan in 1859, Smith was descended from Revolutionary War General Israel Putnam and Henry Alden, the Virginian. Shortly after the family moved to Grand Rapids, Smith’s father died. Twelve-year-old William was forced to drop out of school and go to work to support the family. He developed his own small street-vending business, a popcorn-selling enterprise. While peddling his product, Smith sang lively tunes as a young friend accompanied him on the banjo. Within less than a year’s time Smith was bringing in $75 a month, nearly double the average American income of the period. It provided the sole support for his family.

Well known in Grand Rapids, the young man’s political career began when he was appointed a pageboy in the Michigan legislature at age 19. During the same period he worked part-time as a correspondent for a Chicago newspaper. After attending law school, Smith became active in the Michigan Republican Party. At age 34 he won a landslide election to Congress and went to Washington in 1895 as one of the youngest members of the House of Representatives.

According to Wyn Craig Wade: “House Republicans soon found him one of their most unpredictable members. On economic issues, such as the high protective tariff, he could be trusted to vote with the party.” But on other matters, particularly those affecting individual liberty, he could “just as well be found leading the Democratic opposition.1 Always highly independent, Smith preferred to chart his own course and, as a consequence, became, according to Wade, “the most politically peculiar and yet ‘most representative representative’”2 in the House.

Smith was also an accomplished orator. His constituents loved him and he was easily reelected to Congress by increasing majorities, eventually running unopposed. In 1903 Smith made a run for the U.S. Senate, but a powerful Detroit family, the McMillans, organized his defeat. In 1906 Smith made another bid. To counter Smith’s campaign the McMillans bought the Detroit Free Press. Smith responded by buying the Grand Rapids Herald, which he used effectively in his statewide campaign. In charge of Smith’s political machine was a young Herald reporter, Arthur H. Vandenberg. Smith beat out two Mc Millan family-backed candidates and was elected by the Michigan legislature to the U.S. Senate. This was prior to the ratification of the 17th Amendment which provided for statewide popular election of U.S. senators.

Although Smith moved cautiously in his new post, he soon demonstrated that he wasn’t any pushover when it came to taking on the plutocratic elite. According to Wade: “Sensing he was on firm ground, he electrified the Senate by forcing from the Aldrich Emergency Currency Bill a railroad bond feature that had been tacked on by the J.P. Morgan interests. Smith was the first Republican who had ever challenged the undisputed sway of Nelson Aldrich, the czar of the Senate, and Aldrich capitulated to Smith’s demand out of shock more than anything else.”3 Aldrich, whose daughter married John D. Rockefeller Jr., is best remembered today for laying the foundation stones for what became legislation creating the Federal Reserve System. (Parenthetically, he was also the namesake of the late New York governor and onetime golden boy of the “Chase Bank Republicans,” Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller.)

At the time, Cosmopolitan magazine, which had just completed a series on senatorial corruption, wrote of Smith: “There is never any doubt as to where he stands on any public question. He is absolutely fearless in the statement of his convictions, and neither party caucuses, nor Senate traditions, nor autocratic chief executives embarrass or intimidate the expression of his honest views.”4

And then came the Titanic. As the news of the disaster swept around the world, Smith remembered a yellowed news clipping that he’d carried in his wallet for 10 years—a poem about a shipwreck. It read in part: “Then she, the stricken hull,/The doomed, the beautiful,/Proudly to fate based/Her brow, Titanic.” An incredible coincidence, indeed.

Smith, like most people, was astounded at the tragedy and believed that something had to be done—to find out why such a disaster could happen. Why did the Titanic—supposedly a triumph of modern technology—sink to the bottom of the North Atlantic? Why did so many people die? Why weren’t there enough lifeboats? Was there negligence on the part of the ship’s crew and its owners and management? These were the questions that Sen. Smith, like millions of others, were asking.

Michael Davie writes: “Smith was put in charge of the Senate inquiry [into the sinking] largely because it was he who inspired it. On Wednesday, April 17, as soon as the scale of the disaster was known, Smith, as a member of the Senate Commerce Committee, introduced a resolution. It directed that a Commerce subcommittee should at once begin to investigate the causes of the wreck. American lives and American property were a considerable consideration relative to the awful event. His resolution was adopted unanimously. Before the day was out, Smith was appointed chairman of the inquiry. He assembled a carefully balanced committee of Republicans and Democrats.”5

(Of interest to modern-day populists: Among those serving on Smith’s committee of inquiry was Sen. Francis Newlands [D-Nev.]. Newlands’ great-grandniece, Anne Newlands Cronin, today serves as secretary of the Board of Policy of Liberty Lobby, the populist Institution in Washington, D.C.)

Again, according to Davie: “Smith was up for reelection that autumn but his motives in pressing for the inquiry do not seem to have been primarily inspired by a desire to win popularity in his home state, since he was confident of victory. He appears to have been genuinely stirred, even outraged, by the disaster besides, it created a rare opportunity of marshaling public opinion behind an investigation into the way the shipping trusts operated.”6

By moving toward an inquiry into the shipping trusts, Senator Smith was figuratively knocking on the door of the international banking establishment and its corporate interests.

The Titanic, you see, was not strictly a “British” liner as stated in the history books. Instead, it was owned, from top to bottom and stem to stern by international corporate and financial interests that were largely anything but English.

Although the White Star Line had been organized and nurtured to success and prominence in the British Isles by the Ismay family, the line had undergone a change in ownership prior to the launching of the Titanic.

According to Wade:

By 1901, virtually all of the major ocean lines were in serious trouble. Competition from new steamship companies, notably from Germany, and a slackening of emigrant traffic were followed by a ruinous rate war. If that were not enough, passenger lists were more and more taken up by nouveau riche tourists—mostly Americans—who demanded increased luxury as well as speed. Both demands required a staggering increase in the outlay of capital in building new trans-Atlantic ships.

At this point, American financier J. Pierpont Morgan took a giant’s step into the picture. Many Americans had been sizing up the financial prospects of overseas markets. Morgan, having bought up American railroads, coal and steel, had now set his sights on something bigger—the Atlantic Ocean. A shipping magnate had asked [Morgan] if it were possible to bring the various North Atlantic steamships under one ownership. “It ought to be,” was Morgan’s laconic reply. Now, at the height of the rate war, Morgan proposed an immense, international trust, predominantly American-owned, which would essentially control all major European shiplines. Morgan’s plan was to end the rate war simply by crushing competition and then fix prices at a comfortable profit.

British citizens were immediately unnerved by the clout inherent in Morgan’s proposal. In the midst of this fear and outrage, the leaders of the Cunard Line succeeded in getting a loan of more than two million pounds from the British government. The result was Cunard’s Lusitania and Mauritania, the largest steamships the world had ever seen, quickly captured the Blue Ribbon for speed across the North Atlantic. After this dazzling achievement by its archrival, White Star’s viability as a competitor with Cunard depended on its submission to the Morgan scheme&hellip

Eventually, Morgan made an offer that the White Star shareholders couldn’t refuse he offered to buy them out at ten times the value of the line’s earnings for the year 1900&hellip Assuaging the deepest British fears, Morgan further assured that ships of the White Star Line, though principally American-owned, would remain reserves of the British navy and could be completely taken over by it in the event of war&hellip The deal between International Mercantile Marine (IMM) and the White Star Line was finalized in December 1902. It was agreed that Bruce Ismay would remain the White Star’s managing director and chair man.7

Ultimately Ismay became president of IMM, but the real power was Morgan and his sponsors.

By a twist of fate, Morgan himself had been scheduled to sail on Titanic’s maiden voyage. He canceled his passage at the last minute, one of several notables to do so. Among them were Robert Bacon, the U.S. ambassador to France, Henry Clay Frick, the Pittsburgh steel magnate, and George W. Vanderbilt of the famed American family.

As British historian Michael Davie has commented:

“Given the intricate nature of Morgan’s combine, it is not surprising that the absoluteness of his control of White Star was not fully appreciated. The Titanic was generally regarded as a British ship. Even Lord Mersey, with his Liverpool background, was taken aback in the [British] Board of Trade inquiry into the Titanic’s sinking when he learned that the White Star Company’s seagoing rules, (under which the Titanic, like all other White Star vessels, had been operating), had been drawn up in the United States.”8

Ironically, at this juncture, there is one other little-known fact about the Morgan interests that is worth noting. Although Morgan was internationally famed as a “robber baron” and as “the world’s most powerful banker,” populist historian Eustace Mullins was perhaps the first (and possibly the only) writer of any consequence to ever point out that the Morgan financial empire was little more than an American-based front for the ever-expanding tentacles of the Rothschild family of Europe.

Thus, in a sense, the Rothschilds themselves were the ultimate owners of the ill-fated Titanic and the shipping line that due to a heady arrogance relative to the ship’s structural capacities sent it to the bottom of the Atlantic. But it was J.P. Morgan, the Rothschild front man, and—even more so—J. Bruce Ismay, scion of the industrious family that created and nurtured the White Star Line, who faced the public’s fury and who were demonized in the press.

Indeed the press of America, Great Britain and other countries had a field day with the Titanic investigation. This highly dramatic tragedy and its aftermath provided “great copy.”

Senator Smith himself was targeted for ridicule in the British press. Its members took umbrage at Smith’s having dared to question British seamanship, competence and integrity. The spectacle of brave British officers and seamen—Titanic survivors—being brought be fore Smith’s inquiry was just too much for the British press to take. But Americans loved it.

What did Smith and his committee achieve in the long run? Michael Davie summarizes the results:

Some changes had already been made by the time the committee reported. Shipping lanes were moved farther south, away from the ice. The U.S. Navy assigned two scout cruisers to patrol the Grand Banks: this was the beginning of the International Ice Patrol. Ismay decreed that in the future no White Star liner would sail without adequate lifeboat accommodation for everyone aboard.

But Smith also did much to prod a reluctant U.S. government into legislative action. The Smith bill laid down new rules about bulkheads, lifesaving equipment, pumps, the number of skilled crewmen for each boat, and the designation of a particular place in each lifeboat for each passenger and member of the crew. The near-anarchy of wireless operation came to an end. All vessels with over 50 passengers must be equipped with a wireless set, with a range of at least 100 miles. All sets must have auxiliary power. Direct communication must be provided between wireless operators and the bridge, and wireless apparatus must be manned day and night. The bill made it a misdemeanor to send up rockets save as distress signals.

Smith also called for new international agreements to regulate sea traffic. The first Safety of Life and Sea conference met in London, between November 12, 1913 and January 20, 1914. This conference produced an unprecedented degree of international cooperation. Many of the measures had been prefigured by the Smith bill.

In the United States, Smith’s efforts eventually led to new laws about lifeboat drills and the training of seamen assigned to lifeboats. Moreover, Smith’s bill took a crack at the trusts. It sought to ensure that all companies carrying passengers in or out of U.S. ports disclose more information than hitherto about their ownership and finances, and brought them under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, which, in theory at least, outlawed conspiracies in restraint of trade and all monopolies. More generally, the public attention first focused on conditions at sea by the Titanic disaster—and deliberately kept on the boil by Smith—helped to produce the LaFollette Seaman’s Act of 1915, which gave the oppressed men of the American mercantile marine, largely foreigners, the rights they had long been denied.9

According to Davie, “This burst of regulation and lawmaking cannot all be ascribed to Senator Smith, but it could not have happened without the climate of opinion he helped to create.”

Having been lambasted in the press, and having seen massive shipping industry reforms as a direct result of the Titanic tragedy, J. Bruce Ismay, scion of the White Star Line family, retired from the IMM shipping trust within a year after the disaster. Having had his unfortunate brush with international fame, he withdrew from public life. He died at his estate in Ireland in 1937, after several years of failing health.

According to Don Lynch, in Titanic, An Illustrated History (Hyperion, New York, 1992):

Those who expected the British inquiry to resolve such issues [why so many lives were lost, etc.] would be disappointed. This investigation was not an attempt to get to the bottom of the story, but to sanitize it and remove its sting. The inquiry was a creature of the vested interests who had most to lose from a full investigation. It was conducted by the British Board of Trade (BOT)—the very government ministry responsible for Britain’s outdated maritime safety laws, including the one that had rated the Titanic as having more lifeboats than required. Apart from protecting itself, the BOT had no interest in seeing the White Star Line found negligent. Any damage to White Star’s reputation or balance sheet would be bad for British shipping—and there was considerable potential for both.

J.P. Morgan, the Rothschild family’s American-based representative, lived little more than a year after the Titanic disaster. His doctor claimed that the negative publicity arising from Senator Smith’s Titanic inquiry had taken a toll on Morgan’s health. He was said to be worth $100 million at his death. This was an immense sum in 1913, but evidently he was not as wealthy as most had perceived.

As for Senator Smith, he easily won reelection in 1912. According to Wade, “From 1913 to 1919 he continued taking bold stands on behalf of fiscal conservatism and social liberalism. Notable for standing up for the rights of black Americans, he led the Senate in approving the Emancipation Proclamation Exposition, in fighting for the rights of black landowners in the South, and in blocking a movement that would have barred black women from suffrage under the Nineteenth Amendment.

“He became ranking member of the Foreign Relations Committee, and was delegated chairman of a select committee to investigate the causes of revolutions in Mexico. One of the unexpected outcomes of his study was indictment of the corruptive effects on Latin America of United States Dollar Diplomacy, which he pronounced ‘only for the benefit of Wall Street.’

“Smith became a vigorous opponent of America’s entry into World War I and a bitter critic of [Woodrow] Wilson’s prewar foreign policy, particularly as it affected Germany. He declared Wilson’s partisanship with Britain ‘obvious’ and his neutrality ‘a sham,’ and argued that sooner or later Germany would be forced to retaliate.”10

Although Smith considered a bid for the Republican presidential nomination in 1916, he abandoned his plans when Michigan’s industrialist-populist Henry Ford won their home state’s backing as its “favorite son.” At this juncture Smith opted to retire from public office, declining to seek reelection in 1918. He returned to his newspaper and took up banking. Sen. Smith died of a heart attack at 73 on October 11, 1932. One reporter remembered the outspoken populist as “the friendliest man in Michigan.”11 Another said Smith brought to the Senate “a new type of aggressive honesty and devotion to principle.”12

A final word. Although he never lived to fight—as he would have—against U.S. entry into the Second World War, Smith was most definitely there in spirit. His protégé and former campaign manager in his first bid for the Senate, ex-newspaper reporter Arthur Vandenberg, now represented Michigan in the U.S. Senate. He became a leader of the anti-interventionist cause. Subsequently, however, largely due to the wooing of Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman during and following the World War II years, Vandenberg moved away from William Smith-style populism and nationalism. But during the period prior to U.S. entry into WWII, Vandenberg did carry on the legacy of his mentor, William Alden Smith. This now all-but-forgotten great figure of the 20th century was indeed a Titanic hero.

Footnotes

- Wyn Craig Wade. The Titanic: End of a Dream. (New York: Penguin Books, 1980), p. 121.

- Ibid., p. 123.

- Ibid., p. 128.

- Ibid., p. 129.

- Michael Davie. Titanic: The Death and Life of A Legend. (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1987), pp. 163-164.

- Ibid.

- Wade, pp. 32-34.

- Davie, pp. 8-9.

- Ibid., pp. 180-182.

- Wade, pp. 450-451.

- Wade, p. 452.

- Ibid.

Taken from The Barnes Review, April 1997: RMS Titanic’s Unsung Hero VOLUME III, NUMBER 3

Share this post

Ancient Tulum: Mayan Capital of High Technology and Ancient White Leadership

re-Spanish Mexico’s ...