Britain’s Balfour Declaration of 1917

By Robert John. Eighty years ago, the British government—through international bankers—brokered away the land and the future of the people of Palestine in order to create a national home for the Jewish people. The president and Congress of the United States underwrote the World War I deal, which would cost Britain mightily and which continues to cost American taxpayers well over $4 billion dollars each year. But in terms of what it will cost in the future, in terms of both U.S. treasure and blood, is incalculable.

As a result of a British government pledge to international Zionists in 1917, millions of Palestinians were dispossessed of their homes and lands and their descendants are today refugees. They have suffered eight decades of the most severe and oppressive military occupation. Thousands have been killed and untold numbers tortured to death. Dozens of Arab towns and villages have been obliterated; replaced by Jewish settlements financed by American taxpayer dollars. The lands, farms, homes and moveable property of Palestinians have been confiscated.1 Water for their farms is diverted to Israeli communal farms, leaving Palestinians literally high and dry, their crops withered and their fields turned to dust.

American airplanes paid for by American taxpayers, piloted by Israelis, have bombed Palestinians and dropped American napalm on Palestinian civilians. During the Palestinian uprising (intifada, literally, “throwing off”), hundreds of children and young people were beaten to death, while thousands more suffered permanent damage from head injuries as a result of clubbings and shootings with “rubber” bullets. A deliberate policy of breaking their legs and arms was instituted by the late General Yitzhak Rabin.

In area wars resulting from the British pledge and its implementation, millions of the Palestinians’ neighbors have been involved. In 1995, retired Israeli Brigadier General Arieh Biroh spoke of Egyptian prisoners taken by his unit in 1956: “We did not know what to do with them. There was no choice but to kill them… This is not such a big deal if you take into consideration that I slept well after having escaped the crematories of Auschwitz.”2

These endless atrocities and violations of human rights, and more, have occurred with the military and political support of the government of the United States of America, and $100 billion from American taxpayers. The ease with which huge military and other Israeli appropriations (monies not expended in the interests of this nation) pass through Congress shouts volumes regarding the cupidity of lawmakers and the media; not to mention the ignorance and indifference of vast numbers of U.S. citizens footing the bills.

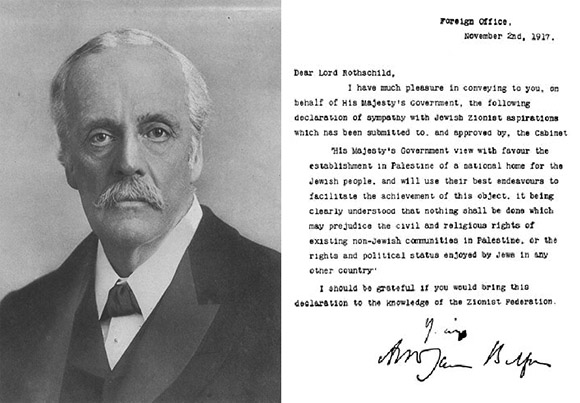

The pledge of the British government—the brief Balfour Declaration—ranks with the most extraordinary documents produced by any government in world history. It took the form of a letter from the Foreign Secretary of the government of His Britannic Majesty King George V, the largest empire the world has ever known, to Lord Rothschild, the leader in Britain of that international banking house.

The noted Jewish author Arthur Koestler wrote that in the letter “one nation solemnly promised to a second nation the country of a third.” More than that, the land was still part of the empire of a fourth, namely Turkey. It read:

Foreign Office,

November 2nd, 1917

Dear Lord Rothschild,

I have much pleasure in conveying to you on behalf of His Majesty’s Government the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations, which has been submitted to and approved by the Cabinet:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement [sic] of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

I should be grateful if you would bring this Declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Elders.

Yours sincerely,

Arthur James Balfour

Seven months had passed since America entered the war. The text of the Balfour Declaration, seemingly so simple, had been prepared over more than a year. It was composed by some of the craftiest of legal draftsmen, including Louis D. Brandeis, a leading advocate of Zionism, who had been confirmed as an associate justice of the U. S. Supreme Court in June 1916. Justice Brandeis had been recommended by Samuel Untermyer (sometimes spelled Untermeyer; it’s the same man), a leading Zionist attorney, to whom President Woodrow Wilson was indebted for political services rendered.

On October 16, 1917, after a conference with “Colonel” Edward M. House, Wilson’s closest adviser, British Ambassador Wiseman had telegraphed to Foreign Secretary Balfour’s private secretary: “Colonel House put the formula before the President, who approves of it but asks that no mention of his approval shall be made when His Majesty’s Government makes formula public, as he had arranged that American Jews shall then ask him for approval, which he will publicly give here.”

Years of scheming were behind the letter’s three paragraphs. Now there were certain courtesies to be effected in moving to the next stage of top-level manipulation. On November 12, 1917, Chaim Weizmann, who would become the first president of a Jewish state in 1948, wrote a letter of thanks to Brandeis:

I need hardly say how we all rejoice in this great event and how grateful we all feeI to you for the valuable and efficient help which you have lent to the cause in the critical hour.

Once more, dear Mr. Brandeis, I beg to tender to you our heartiest congratulations not only on my own behalf but also on behalf of our friends here and may this epoch-making be a beginning of great work for our sorely tried people and also of mankind.

The other principal Allied governments were approached by the Zionist representative, Nahum Sokolow, with requests for pronouncements similar to the Balfour Declaration. The French simply supported the British government in a short paragraph on February 9, 1918. Italian support was contained in a note dated May 9, 1918 to Sokolow by its am bas sador in London, in which he stressed the religious divisions of communities, grouping “a Jewish national centre” with “existing religious communities.”

On August 31, 1918 President Wilson wrote to Rabbi Stephen Wise “to express the satisfaction I have felt in the progress of the Zionist movement since Great Britain’s approval of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” Brandeis joined in Zionist delight at the president’s endorsement and wrote: “Since the president’s letter, anti-Zionism is pretty near disloyalty and non-Zionism is slackening.” Non-Zionist Jews now had a hard time if they wanted to disseminate their views; if they could not support Zionism they were asked to remain silent.

On June 30, 1922 the following resolution was adopted by the United States Congress:

Resolved by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled. That the United States of America favors the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which should prejudice the civil and religious rights of Christians and all other non-Jewish communities in Palestine, and the holy places and religious buildings and sites in Palestine shall be adequately protected.

The Resolution was introduced by Hamilton Fish (R-N.Y). His interpretation of this action was clarified 38 years later, when the World Zionists held their 25th Congress in Jerusalem. David Ben Gurion, as prime minister of Israel, stated in his address: “Every religious Jew has daily violated the precepts of Judaism by remaining in the Diaspora.” Citing the authority of the Jewish sages, Ben Gurion added: “Whoever dwells outside the land of Israel is considered to have no god.”

He continued: “Judaism is in danger of death by strangulation. In the free and prosperous countries it faces the kiss of death, a slow and imperceptible decline into the abyss of assimilation.”

Mr. Hamilton Fish replied: “As author of the first Zionist Resolution patterned on the Balfour Resolution, I denounce and repudiate the Ben Gurion statements as irreconcilable with my Resolution as adopted by Congress, and if they represent the government of Israel and public opinion there, then I shall disavow publicly my support of my own Resolution, as I do not want to be associated with such un-American doctrines.”

The Balfour Declaration is a model of manipulation of people in power, of leverage, of the subvention of national policies to serve special interests that is demonstrated repeatedly, and often clandestinely, in public affairs.

Leaflets containing the World Zionist Congress message were dropped by air on German and Austrian towns and widely distributed through the Jewish belt from Poland to the Black Sea. It was an epochal triumph for Zionism and, some believe, for Jews.

It was decided by the World War I British commander in Palestine, Lord Allenby, that the “Declaration” should not then be published there, as his forces were still south of the Gaza-Beersheba line. They were not published until after the establishment of the Civil Administration in 1920.

Why was the “Declaration” made a year before the end of what was called the Great War? The study of this event provides models of the insider influence that is behind many major policies of governments up to today. Only a sample of the details which I documented in The Palestine Diary (New World Press, revised ed. 1972, 2 vols.) can be given here.

The British people were told at the time that their government’s promise to Lord Rothschild was given as a return for a debt of gratitude which they were supposed to owe to the Zionist leader, Chaim Weizmann, a Russian-born immigrant to Britain from Germany.

This literal horse chestnut propaganda is still carrying on its mission of deception. A review of Bernard Dixon’s book Power Unseen in Scientific Amer i can (Aug. 1994), repeats the author’s recounting of the old canard that the wartime prime minister put to rest long ago. It maintained that Britain’s 1917 Balfour Declaration to support the establishment of a national home for the Jews in Palestine was extended in gratitude for Weizmann’s bringing to Britain from Germany a process of fermentation of horse chestnuts he was said to have invented. Its purpose was to produce acetone for guncotton, used in enormous quantities in WWI by the Ministry of Munitions.

This story was offered to the press because the real motivation could not be revealed at the time. After World War One, Prime Minster Lloyd George wrote in his Memoirs of the Peace Conference (where, as planned many years before, the Zionists were strongly represented):

There is no better proof of the value of the Balfour Declaration as a military move than the fact that Germany entered into negotiations with Turkey in an endeavor to provide an alternative scheme which would appeal to Zionists. A German-Jewish Society, the V.J.0.D., was formed, and in January 1918, Talaat, the Turkish Grand Vizier, at the instigation of the Germans, gave vague promises of legislation by means of which “all justifiable wishes of the Jews in Palestine would be able to meet their fulfillment.”

Another most cogent reason for the adoption by the Allies of the policy of the Declaration lay in the state of Russia herself. Russian Jews had been secretly active on behalf of the Central Powers from the first; they had become the chief agents of German pacifist propaganda in Russia. By 1917 they had done much in preparing for that general disintegration of Russian society, later recognized as the Revolution. It was believed that if Great Britain declared for the fulfillment of Zionist aspirations in Palestine under her own pledge, one effect would be to bring Russian Jewry to the cause of the Entente [European Allies].

It was believed also that such a declaration would have a potent influence upon world Jewry outside Russia, and secure for the Allies the aid of Jewish financial interests. In America, their aid in this respect would have a special value when the Allies had almost exhausted the gold and marketable securities available for American purchases. Such were the chief considerations which, in 1917, impelled the British government towards making a contract with Jewry (p. 726).

The government had been headed by Lloyd George, an ambitious and aggressive Welsh politician, since December 1916, when his predecessor Herbert H. Asquith was ousted by a coup de main. George had been legal counsel for the Zionists, and while Minister of Munitions, had assured Chaim Weizmann that “he was very keen to see a Jewish state established in Palestine.” George’s choice as his foreign secretary was Arthur Balfour, already known for his Zionist sympathies.

Was the Balfour Declaration made by the British people through their elected Parliament? Parliaments and Congresses may cobble some of the fabric of history, but its designs and the big decisions, even of “democracies,” are made by a very few people with special interests.

Winston Churchill said:

“The Balfour Declaration must, therefore, not be regarded as a promise given from sentimental motives; it was a practical measure taken in the interests of a common cause at a moment when that cause could afford to neglect no factor of moral or material assistance.” Speaking in the House of Commons on 4 July 1922, Winston Churchill asked rhetorically, “Are we to keep our pledge to the Zionists made in 1917? Pledges and promises were made during the war, and they were made, not only on the merits, though I think the merits are considerable. They were made be cause it was considered they would be of value to us in our struggle to win the war. It was considered that the support which the Jews could give us all over the world, and particularly in the United States, and also in Russia, would be a definite palpable advantage. I was not responsible at that time for the giving of those pledges, nor for the conduct of the war of which they were, when given, an integral part. But like other members I supported the policy of the War Cabinet. Like other members, I accepted and was proud to accept a share in those great transactions, which left us with terrible losses, with formidable obligations, but nevertheless with unchallengeable victory.”

If these statements were true, could Germans blame “the Jews” for their defeat in the Great War? What had the Zionists done for Britain? Were there grounds for Lloyd George’s allegation that Germany was considering a bid for Jewish support by a pro-Zionist declaration? These are matters of opinion for further historical analysis. But a Jewish national entity in Palestine was a goal planned by Zionists years before.

From the beginning of the war, the German Ambassador in Washington, Count Bernstorff, was provided, by the Komitee für den Osten, with an adviser on Jewish Affairs (Isaac Straus). When the head of the Zionist Agency in Constantinople appealed in the winter of 1914 to the German Embassy to do what it could to relieve the pressure on the Jews in Palestine, it was reinforced by a similar appeal to Berlin from Bernstorff.

In November 1914, therefore, the Ger man Embassy in Constantinople received instructions to recommend that the Turks sanction the re-opening of the Anglo-Palestine Company’s Bank—a key Zionist institution. In December the embassy made representations which prevented a projected mass deportation from Turkey of Jews of Russian nationality. In February 1915 German influence helped to save a number of Jews in Palestine from imprisonment or expulsion, and “a dozen or twenty times” the Germans intervened with the Turks at the request of the Zionist office in Turkey. The German representations reinforced those of the American ambassador in Turkey (Henry Morgenthau Sr., father of FDR’s treasury secretary). Moreover, both the German consulate in Palestine and the head of the German military mission there frequently exerted their influence on behalf of the Jews.

As the reader will ascertain, a competition for Jewish support between Britain and Germany was being played out. We see its likeness in American politics, as candidates and office holders are pressured to commit themselves to ever-higher levels of support of Israel or other Jewish interests.

The traditional Judaic position, still faithfully followed by some interpreters of the Talmud, is that the Messiah will establish his kingdom in Jerusalem and Jews are forsworn by the Almighty “not to use human forces to bring about the establishment of a state, not to rebel against the nations but to remain loyal citizens, not to leave exile ahead of time. Even if the land be given to us by all of the nations, we are not allowed to accept it. To violate the oaths would result in your flesh made prey as the deer and the antelope in the forest” (Talmud Tractate Ksubos III).

Free thought, peasant liberation and constitutional reform were in the air of mid-19th century eastern Europe, and in 1861 serfdom was abolished in Russia. The spread of emancipation, in cluding auto-emancipation, spread across Europe from west to east.

It was in Minsk, a city of 30,000 inhabitants of whom the great majority were Jews, known among the eastern Jews as “a city and mother in Israel,” that Chaim Weizmann went to school. And in the ferment which Weizmann called a “folk awakening” of the Jewish and Russian masses, the Jewish nationalist dream competed with the Jewish internationalist idea. One led to “Zionism,” a term coined by Dr. Nathan Birnbaum about 1893. The other to the formation in 1897 of the pre-communist “The Jewish Revolutionary Labor Organization (Der Algemeyner Idisher Arbeter Bund). Both movements had in common an idea of “the dignity of manual labor.”

Though “Zion” referred to a geographical location, it functioned as a utopi an conception in the myths of traditionalists, modernists and Zionists alike. It was the reverse of everything rejected in the “Dispersion,” whether oppression or assimilation. The emphasis was on agricultural settlement. Phi lan thropist Baron Edmond de Roths child supported settlement in Palestine, while Baron de Hirsch sponsored settlement mainly in agricultural colonies in Argentina, and also in the United States.3

The dichotomy between Jewish nationalism and internationalism was addressed by Theodore Herzl (1860-1904). He was of Hungarian Sephardic descent on his rich father’s side, and published Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) in Vienna in 1896. His anti-assimilationist dictum that “Zionism is a return to the Jewish fold even before it is a return to the Jewish land,” was an expres sion of his own experience. It was extended into the official platform of Zionism as the aim of “strengthening the Jewish national sentiment and national consciousness.”

In his diary Herzl describes submitting his draft proposals to the Rothschild Family Council, noting “I bring to the Rothschilds and the big Jews their historical mission.” The policy for supporters and opponents would be, “I shall welcome all men of goodwill—we must be united—and crush all those of bad.”

Herzl read his manuscript addressed to the Rothschilds to a friend, Meyer-Cohn, who said: “Up till now I have believed that we are not a nation—but more than a nation. I believed that we have the historic mission of being the exponents of a universalism among the nations and therefore were more than a people identified with a specific land.”

Herzl replied: “Nothing prevents us from being and remaining the exponents of a united humanity, when we have a country of our own. To fulfill this mission we have to remain literally planted among the nations who hate and despise us. If in our present circumstances, we wanted to bring about the unity of mankind independent of national boundaries, we would have to combat the ideal of patriotism. The latter, however, will prove stronger than we for innumerable years to come.”4

It was Herzl who created the first Zionist Congress, held August 29-31, 1897 at Basel, Switzerland. There were 197 “delegates,” including orthodox, nationalist, liberal, atheist, culturalist, anarchist, socialist and some capitalist. “We want to lay the foundation stone of the house which is to shelter the Jewish nation,” and “Zionism seeks to obtain for the Jewish people a publicly recognized, legally secured homeland in Palestine,” declared Herzl.

Another leading figure who addressed the Congress was Max Nordau, a Hungarian Jewish physician and author, who delivered a polemic against assimilated Jews. “For the first time the Jewish problem was presented forcefully be fore a European forum,” wrote Weiz mann. But the Russian Jews thought Herzl was patronizing them as Ashkenazim. They found his “western dignity did not sit well with our Russian-Jewish realism; and without wanting to, we could not help irritating him.”

In conversation with a delegate at the First Congress, Herzl said (as reported more than 20 years later in the American Jewish News of March 7, 1919):

It may be that Turkey will refuse or be unable to understand us. This will not discourage us. We will seek other means to accomplish our end. The Orient question is now the question of the day. Sooner or later it will bring about a conflict among the nations. A European war is imminent—the great European War must come. With my watch in hand do I await this terrible moment. After the great European war is ended the Peace Conference will assemble. We must be ready for that time. We will assuredly be called to this great conference of the nations and we must prove to them the urgent importance of a Zionist solution to the Jewish Question. We must prove to them that the problem of the Orient and Pales tine is one with the problem of the Jews—both must be solved together. We must prove to them that the Jewish problem is a world problem and that a world problem must be solved by the world. And the solution must be the return of Palestine to the Jewish people.”

A few months later, in a message to a Jewish conference in London, Herzl wrote that “the first moment I entered the Movement my eyes were directed towards England, because I saw that by reason of the general situation of things there it was the Archimedean point where the lever could be applied.” Herzl showed his respect for London as the world’s financial center by causing the Jewish Colonial Trust, which was to be the main financial instrument of his movement, to be incorporated in 1899 as an English company.

In Turkey, as in Germany, some native Jews were resentful of the attempt to segregate them as Jews and were opposed to the intrusion of Jewish nationalism in their domestic affairs. Yet some of those engaged in the work, notably Vladimir (Zev) Jabotinsky (1880-1940), came to despair of success so long as the Ottoman Empire controlled Palestine. They henceforth pinned their hopes on its collapse.

At the 10th Congress in 1911, David Wolffsohn, who had succeeded Herzl, said in his presidential address that what the Zionists wanted was not a Jewish state but a homeland. Max Nordau denounced the “infamous traducers,” who alleged that “the Zionists wanted to worm their way into Turkey in order to seize Palestine. It is our duty to convince [the Turks] that they possess in the whole world no more generous and self-sacrificing friends than the Zionists.”

The mild sympathy which the emerging Young Turks had shown for Zionism was replaced by suspicion as growing national unrest threatened the Ottoman Empire, especially in the Balkans. Zionist policy then shifted to the Arabs, so that they might think of Zionism as a possible counter balance against the Turks. Zionists soon observed that their reception by Arab leaders grew warmer as the Arabs were disappointed in their hopes of gaining concessions from the Turks, but cooled swiftly when these hopes revived. The more than 60 Arab parliamentary delegates in Constantinople and the newly active Arabic press kept up “a drumfire of complaints” against Jewish immigration, land purchase and settlement in Palestine.

The Turks were doing all they could to keep Jews out of Palestine. But this barrier was covertly surmounted, partly due to the venality of Turkish officials, (as delicately put in a Zionist report—“it was always possible to get ’round the individual official with a little artifice”); and partly to the diligence of the Russian consuls in Palestine in protecting Russian Jews and saving them from expulsion.

But if Zionism were to succeed in its ambitions, Ottoman rule of Palestine must end. Arab independence could be prevented by the intervention of England and France, Germany or Russia. The Eastern Jews hated Czarist Russia. With the entente cordiale in existence, it was to be Germany or England, with the odds slightly in Britain’s favor in potential support of the Zionist aim in Palestine, as well as in economic and military power.

On the other hand, Zionism was attracting some German and Austrian Jews with important financial interests. It had to take into account strong Jewish anti-Zionist opinion in England. The concern of the majority of rich English Jews was not allayed by articles in the Jewish Chronicle, edited by Leopold Green berg, pointing out that in the Basel program there was “not a word of any autonomous Jewish state.” In Die Welt, the official organ of the movement, an article by Nahum Sokolow (then the general secretary of the Zionist Organization) protested that there was no truth in the allegation that Zionism aimed at the establishment of an independent Jewish state.

Even at the XI Congress in 1913, Otto Warburg, speaking as chairman of the Zionist Executive, gave assurances of loyalty to Turkey, adding that in colonizing Palestine and developing its re sources, Zionists would be making a valuable contribution to the progress of the Turkish Empire.

Jewish opposition to political statist Zionism came not only from religious sources, but from many Jews of great wealth in Europe and the U.S.A. The Jewish national idea foreshadowed an alienation from the societies in which they were exercising great economic and political power. From Scandinavia, where the Wallenbergs were looking to eventual control of industry through leverage, to Baron Sonnino in Italy, Europe was open to Hof Juden—Court Jews who lived like princes. Benjamin Disraeli had been British prime minister and Lord Cassel was part of the circle of Edward VII. Prince Otto von Bismarck, founder of the Second German Reich and German chancellor, had appointed Jewish banker Gerson von Bleichröder as his confidential agent, giving him power of administration of the Bismarck properties. The international banking houses of Lazard Freres, J.&W. Seligman, Speyer Brothers and M.M. Warburg, Schiff, were all conducting major operations in the United States. In 1908 Paul Warburg had come to the United States from Germany, abetted the setting up of the Federal Reserve System of banking in 1913, and became one of the bank’s first board members. Only in Russia were Jews blocked from the top echelons of power, although Jews controlled the grain trade from Ukraine.

Through their banking houses in London, Paris, Naples and Vienna the Rothschilds were able to cause crises for governments, and make money.5 Do these facts support Lloyd George’s explanation for his government’s pledge to Lord Rothschild? The influence of the 3,000,000 Jews in America was important to the question of the country’s intervention or non-intervention in the war, and in regard to the provision of military supplies. The great majority of Jews in the U.S. represented the one-third of the Jews of Eastern Europe, including Russia, who had left their homelands and come to America between 1880 and 1914. Many detested the alliance composed basically of Britain, France, and Czarist Russia, and wished to see it destroyed. But of these Jews, not more than 12,000 were enrolled mem bers of the Zionist Organization at the time of the First World War. For the (German) Jewish banking elite in America, the evidence points to the 1917 Russian revolution as being the most weighty factor relative to their support.

For some Germans and others after World War I, the weight given the Balfour Declaration by British Prime Minister Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, and other powerful figures relative to critical Jewish support toward Allied victory, lent credence from the highest authority to anti-Jewish feeling. Is this a way of understanding subsequent German susceptibility to discrimination against Jews following the Great War? The integrating relationship between German Jews and non-Jews was disrupted, a relationship that had been so firm that many German Jews could hardly accept that it had been jeopardized.

For the Jews, there has been what the Jewish Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm calls “the invention of tradition” in Israel; Zionist periodization of Jewish history. Specifically, the 2,000-year period when Jews were a small religious minority in Palestine was suppressed and denigrated. The nationalist movement in modern times was linked with ancient periods of political sovereignty.

“Zionist commemorative narrative constructs a symbolic bridge between Antiquity and the modern period, emphasizing their affinity and distancing both from Exile [Zerubavel, p.32].”6The vast majority of Jews have not immigrated to Israel, but it is used as a fulcrum for the application of international power.

Arnold Toynbee, who probably drafted the document on British commitments for the inner group at the Versailles Peace Conference, went on to become one of the century’s outstanding world historians. He wrote in Vol ume VIII of his great A Study of History: (pp. 289-290):

The Jews’ immediate reaction to their own experience was to become persecutors in their turn for the first time since A.D. 135, and this at the first opportunity that had arisen for them to inflict on other human beings who had done the Jews no injury, but who happened to be weaker than they were, some of the wrongs and sufferings that had been inflicted on the Jews.

In A.D. 1949, the Jews knew from personal experience what they were doing, and it was their supreme tragedy that the lesson learned by them from their encounter with the Nazi Gentiles should have been not to eschew but to imitate some of their evil deeds that the Nazis had committed against the Jews.

This judgment made him the target for attacks familiar to anyone who has dared to tell the truth on these issues. The attacks were ad hominem rather than relevant to his subject matter. In 1960 he wrote in Volume XII (p. 267):

The seizure of the houses, lands, and property of the 900,000 Palestinian Arabs who are now refugees is on a moral level with the worst crimes and injustices committed, during the last four or five centuries, by Gentile Western European conquerors and colonists overseas. This is still my judgment on the Zionist movement’s record in Palestine since it began to resort to violence there.

As for Britain, Oxford historian Eliza beth Monroe’s study, Britain’s Moment in the Middle East (Chatto & Windus, 1963, p.43), concludes, “Measured by British interests alone, the Balfour Declaration was one of the greatest mistakes in our imperial history.” William Yale was the U.S. State Department’s special agent in the Near East during World War I. He told this writer on May 12, 1970 that Woodrow Wilson had asked him in 1919 to interview persons who might be influential to the future of the area.

Yale interviewed Chaim Weizmann, and asked him what he would do if the British did not support the Balfour Declaration for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Weizmann pounded his fist on the table and the teacups jumped. “If they don’t,” he said, “we’ll smash the British Empire as we smashed the Russian Empire.”

And the Rothschilds? They have led from behind and through “fronts,” as first dictated to the family by patriarch Meyer Amschel Rothschild, nearly 250 years ago. The late Ben Freedman showed me a report on the estimated value of the mineral deposits of the Dead Sea7 prepared for Lord Rothschild in 1917. This was at a time when Lord Mond controlled nickel, the Guggenheims controlled copper, Lord Montague controlled Anglo-Dutch oil, and Oppenheimer monopolized De Beers diamonds and South African gold.

President Franklin Roosevelt’s son-in-law, Colonel Curtis Dall, who had been with Wall Street’s Lehman bankers in the 1930s, refers to this geological report, made public in 1923, in his book which he gave me, Israel’s Five Trillion Dollar Secret, published privately in 1977. “The well-veiled objective of the Zionists backed by the Rothschilds’ financial interests was to acquire valid title to the Dead Sea and its vast, inexhaustible deposits of potash and other valuable minerals, estimated by experts to be worth several thousand billion dollars”(p11).

A letter from Lord Rothschild in support of Israel and against the Palestinian Liberation Organization was published in the New York Times of September 13, 1970 and for 20 years no U.S. government would “talk” to the PLO.

Coinciding with the 1,200th anniversary of Frankfurt am Main, members of the Rothschild family empire gathered there in February 1994 in a building that belonged to them in the 19th century and that is now a Jewish museum. German Chancellor Helmut Kohl visited and paid tribute to them. Their importance was recognized in 1917 at great power levels.

Now, in the twilight of this awesomely destructive 20th century, are they the unseen directors of the Bilderberg Group and the Trilateral Commission that set the major extra-parliamentary and extra-congressional decisions regarding our present and future?

Footnotes

Encyclopedia of the Palestine Problem by Issa Nakhleh, N.Y. International Books, 1991, vol. 1, Ch. 11. New York Times, August 21, 1995, A5. Jewish Agricultural Colonies in New Jersey, 1882-1920, by Ellen Eisenberg, Syracuse University Press, 1995. The Diaries of Theodore Herzl. Ed. M. Lowenthal, N.Y. Grosser & Dunlap, 1962, p. 63. An example between the World Wars is given by Frederic Morton in his 1961 book, The Rothschilds (N.Y., Atheneum, p. 251). Extreme currency fluctuations in 1925 were managed by the Rothschilds. “With the French house in the lead (Baron Edouard was director of the Bank of France), they had organized an international syndicate that stretched from J.P. Morgan in New York to the Baron-Louis-controlled Creditanstalt in Vienna. Everywhere, at a pre-arranged signal, the Rothschild syndicate began to depress pounds and push up francs. As in the past, nobody could withstand such wealth juggled with such split-second skill.” Recovered Roots: Collective Memory and the Making of Israeli National Tradition, by Yael Zerubavel, Chicago: University of Chicago, 1995. In 1996 a German company signed a contract in Israel for extraction of magnesium from the Dead Sea.Taken from The Barnes Review, January 1997: The Balfour Declaration VOLUME III, NUMBER 1

Share this post

Ancient Tulum: Mayan Capital of High Technology and Ancient White Leadership

re-Spanish Mexico’s ...