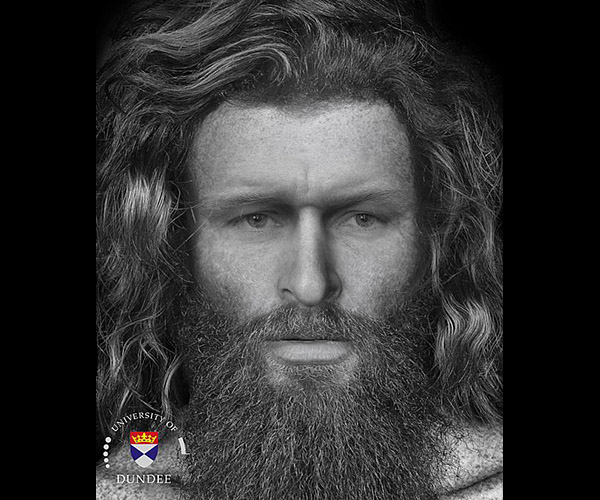

Researchers at the University of Dundee in Britain have successfully reconstructed the face of a Pictish man for the first time, offering a valuable insight in the racial ancestry of this otherwise mysterious people who were the original inhabitants of Scotland—and who were so feared by the Romans that the famous Hadrian’s Wall was built to keep them out of the Empire.

The facial reconstruction was made after archaeologists excavating a cave in the Black Isle uncovered the remains of a man who had been murdered more than 1,400 years ago.

The scientists, all from the Rosemarkie Caves Project had been expecting to find some evidence of human occupation of the cave extending back over a long period of time, but they were astonished to find the skeleton of a man buried in a recess of the cave, covered in a layer of sand, a press statement said.

The bones were sent to an expert forensic anthropologist whose team have been able to describe in detail the injuries he sustained as well as digitally reconstruct what he looked like.

A bone sample sent for radiocarbon dating indicates that he died sometime between 430 and 630 A.D., commonly referred to as the Pictish period in Scotland.

The team of archeologist from the North of Scotland Archaeological Society had to dig through a number of layers relating to cave use since the 20th century before finding evidence that the cave had been used for iron-smithing during the Pictish period.

Hearths and extensive iron-working debris indicate that the cave was selected specifically for this use, but the totally unexpected find of the skeleton of a man gave the cave a completely different significance.

The burial was located in an alcove of the cave, near the metal-working area. The body had been placed in an unusual cross-legged position, with large stones holding down his legs and arms. Prior to its discovery, there had been nothing to suggest that it was there.

The remains were sent to Professor Dame Sue Black, director of the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification at the University of Dundee, and from her extensive experience of analysis of human remains was able to compile a detailed account of how the man died.

“This is a fascinating skeleton in a remarkable state of preservation which has been expertly recovered. From studying his remains we learned a little about his short life but much more about his violent death. As you can see from the facial reconstruction he was a striking young man who was sadly cut down in his prime by brutal interpersonal conflict. We have identified at least 4 or 5 impacts that resulted in fracturing to his face and skull,” she was quoted as saying.

Steven Birch, a local professional archaeologist and volunteer leader of the excavation, said that the style of the death, which included considerable ‘overkill,’ was “reminiscent of the Iron Age bog bodies, examples of which had been pinned down in watery pools using wooden stakes and hurdles.”

The cave excavation has also provided information about the more recent past, including objects left behind by occupants and temporary travelers living inside the cave 200 to 300 years ago. Evidence from this later period suggests that the inhabitants were making, or repairing, leather shoes, possibly for distribution to local communities on the Black Isle.

Ongoing specialist analysis on the skeleton and artefacts from the cave is expected to provide more details of the man’s place of origin and significance as well as provide more information about the cave’s archaeological and historical importance.