A series of remarkable discoveries in a 2,600-year-old burial chamber located in southern Germany have revealed once again that early Europeans were in fact considerably more advanced than often thought.

The discoveries—revealed in a new paper published in the February 2017 edition of the Antiquity journal, (The ‘Keltenblock’ project: discovery and excavation of a rich Hallstatt grave at the Heuneburg, Germany) include a richly furnished grave of an elite woman from the Hallstatt period.

The grave was discovered close to the Heuneburg, the earliest proto-urban settlement north of the Alps.

Dendrochronological analysis of timbers from the grave chamber dates the burial to 583 BC, the earliest of a series of such burials north of the Alps and a key anchor in the absolute chronology of the Early Iron Age in Europe, the paper said.

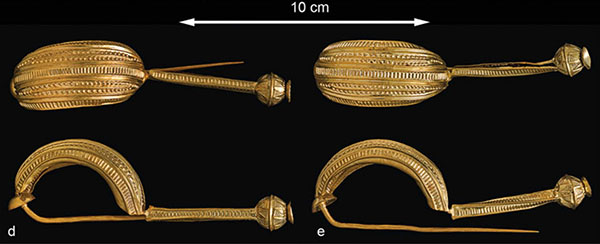

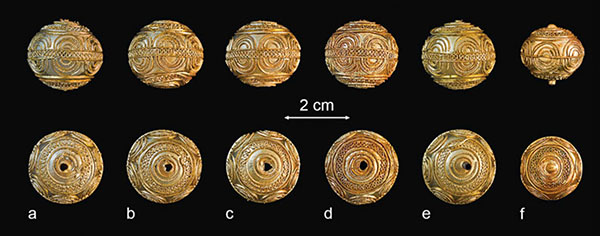

The woman was adorned with gold, bronze, jet and amber jewelry; gold filigree objects, amber fibulae and items of horse-head armor which suggest close connections south of the Alps.

An infant female burial close to the main grave included gold jewelry made for a child but similar to that of the woman.

The goods discovered in the grave indicates that “there were craftsmen working in the early Celtic centers north of the Alps who learned their crafts south of the Alps,” according to archaeologist Dirk Krausse of the Archaeological State Office of Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

Previous research has established that speakers of Celtic languages inhabited parts of Europe as early as 3,300 years ago. Celtic iron makers appeared in Central Europe by around 2,700 years ago—marking the beginning of that region’s Iron Age—and founded what is now called the Hallstatt culture.

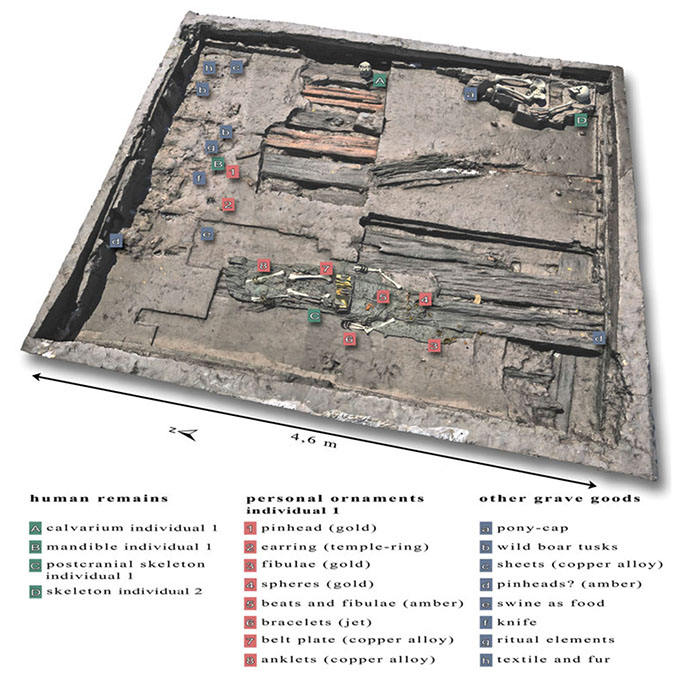

The grave and a smaller adjoining burial lie in a German cemetery situated across the Danube River from an early Iron Age hill fort called the Heuneburg.

Along with yielding insights into long-distance trade and the timing of Europe’s first Iron Age cities, these graves provide the earliest evidence of Hallstatt people elaborately interring women and even children, Krausse and colleagues report in the February Antiquity.

While surveying earthen mounds covering graves at the German site in 2005, Krausse’s team noticed a gold-plated bronze brooch fragment lying on the ground. An excavation revealed that the brooch came from the grave of a 2- to 4-year-old child whose skeleton was surrounded by gold and gold-plated jewelry.

It turned out that the child’s grave was an addition to a larger burial chamber. Because farming activity threatened the site, cranes were used in 2010 to hoist out the chamber and surrounding soil in a block weighing 80 metric tons. Researchers excavated the tomb at Krausse’s facility.

Planks of oak and silver fir formed the chamber. Comparisons of growth rings in the planks with previously dated tree rings in the region indicate that the tomb was built in 583 B.C.

Previous excavations over the past decade had suggested that the Heuneburg and several other early Iron Age settlements in Germany and France were the first cities north of the Alps, but the grave provides the most precise date yet.

Prior to this find, settlements dating to between 2,200 and 2,000 years ago have traditionally been considered the first Central European cities.

Inside the chamber, the team discovered a 30- to 40-year-old woman’s headless skeleton. Her lower jaw and skull were found at two other spots in the grave. Objects placed on and around the skeleton included gold, bronze, amber and jet jewelry and brooches. Decorative styles of some items showed Mediterranean influences.

Researchers also found two pairs of boar tusks mounted on large pendants. Each pair of tusks curves around two bronze strips and bronze bells hanging from a smaller pendant.

Another woman’s skeleton and pieces of bronze jewelry rested in a corner of the chamber. It’s unclear whether both bodies were buried at the same time.

A decorated bronze sheet found near the second skeleton’s feet was a piece of armor, called a chamfron, that covered a horse’s forehead, the researchers say. Traces of plant netting and fur preserved on the inside surface of the sheet come from padding, they suspect. CT scans revealed remains of an iron horse bit at one end of the sheet, where it fit in the mouth.

This is the first chamfron found at a Hallstatt site. It resembles horse armor from around the same time found in several Mediterranean cultures, Krausse says.

“The ?nds from the woman’s and child’s graves from Bettelbühl now demonstrate that the Mediterranean mud-brick architecture is only one indicator of the importance of the Heuneburg in the continental exchange of raw materials, goods, information and services across the Alps and beyond,” the paper said.

“It seems that, in the early sixth century, masterbuilders acquainted with masonry and mud-brick architecture were not the only craftspeople with knowledge of distant techniques working on the Heuneburg. The gold filigree objects, the amber fibulae and the horse’s chamfron each demonstrate much closer connections with the area to the south of the Alps than was previously realized.”