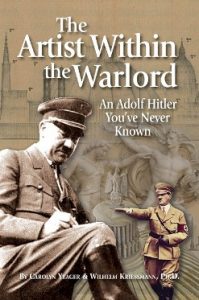

The Artist Within the Warlord

A Book Review

By R.T. Sloane, in Inconvenient History, Vol. 10, No. 2 (spring 2018), published April 5, 2018.

Do we need a reappraisal of Adolf Hitler? Yes, we do. Though the so-called factual basis of the Holocaust has been debunked by revisionists … The homicidal gas chambers, gone … The intention and plan to kill all of Europe’s Jews, never found, doesn’t exist … The 6,000,000 murdered Jews … an impossible fantasy number used again and again since before WWI … yet in spite of the loss of all that, we’re still left with the commonly-held belief in a criminal Adolf Hitler.

Do we need a reappraisal of Adolf Hitler? Yes, we do. Though the so-called factual basis of the Holocaust has been debunked by revisionists … The homicidal gas chambers, gone … The intention and plan to kill all of Europe’s Jews, never found, doesn’t exist … The 6,000,000 murdered Jews … an impossible fantasy number used again and again since before WWI … yet in spite of the loss of all that, we’re still left with the commonly-held belief in a criminal Adolf Hitler.

The justification for this rests on a vague notion that Hitler was a “bad guy” and therefore we don’t want any more Hitlers to get power. This notion is generally based on the idea that nationalism is bad (encourages wars), democracy is good (encourages cooperation), populism is dangerous (encourages mob rule). With such beliefs, there is little incentive to reassess the poisoned popular portrayal of this man in light of new or other information.

A book has just come out that can be classed as one of the other portraits of Hitler the man. Back in 1977, Adolf Hitler’s architect, Munich-born Hermann Giesler published his 500-page memoir titled Ein Anderer Hitler (Another Hitler), after which it remained untranslated into other languages and little known outside Germany. That is, until the translations by Wilhelm Kriessmann Ph.D. and Carolyn Yeager were turned into the book I’m reviewing here. The Artist Within the Warlord: An Adolf Hitler You’ve Never Known is mostly comprised of the last one hundred pages of Giesler’s memoir, dealing with Giesler’s time as Hitler’s guest at the various Fuehrer headquarters between 1940-1945. In these pages, we learn of a Hitler who, though he was forced to wage limited war to bring back the Germany that existed prior to the Great War and the robbery by the Versailles Treaty—a high priority for him—was yet always seeking peace so he could accomplish the architectural restructuring of German cities according to his long-held vision.

Kriessmann and Yeager’s book begins with the short flight to Paris from the Western military headquarters at Bruly de Peche on June 22. 1940, on the eve of the signing of the armistice after the German victory over France. Hitler had already planned this “sight-seeing” trip before the French campaign began and had promised Giesler, architect Albert Speer and sculptor Arno Breker that he would take them along. The purpose was to look at the most important architectural sites in Paris in advance of the planning of major renovation to the city centers of Berlin and Munich. Hitler is seeing everything with an eye to how the architecture and street layouts work in Paris and how they will do it in their German cities. Among Hitler’s spoken words that Giesler records from this trip, one statement sticks with me:

“Planning our architecture, we will aim at a classicism of stricter, sharper forms, according to our character.” (p. 17)

Hitler was as serious as can be about the city-building he wanted to do. Giesler leaves us in no doubt that Adolf Hitler was a true, a genuine artist. This runs throughout the book and others have reported the same thing. So this is one aspect of his personality, a very important one, that is disregarded in the mainstream presentation of him. Another one is his humanism, and another his kindness and thoughtfulness.

His humanism is seen on a number of occasions in the book, but particularly in regard to Dunkirk. In June 1940, Hitler saw the British as decisively beaten and the possibility of reaching a peace agreement in the West, enabling him to concentrate his forces in the East as he wished to do. On humanitarian grounds, he didn’t like the idea of destroying or capturing and holding in poor conditions what turned out to be around 350,000 British soldiers. He had also been misinformed that there were influential men in Britain who wanted to end the war with Germany. (There were some but they had lost their influence by then.) In addition, he was desirous of getting the conflict resolved before the United States entered into it, which he knew Roosevelt was working toward. Based on all this, plus real military considerations by his top advisers, he made his Dunkirk decision. He told Giesler in 1942:

“And did not a slight possibility of peace still exist, even though a vague one, which I might have obstructed by a pitiless defeat of the Dunkirk army?” (p. 49)

But he was let down on that and nothing materialized from it. When he was forced to invade the Soviet Union in a preemptive strike, without having achieved peace in the West, he knew he must defeat the Red Army quickly, and so laid down much harsher guidelines for the battles and rules for dealing with political commissars, saboteurs and irregular fighters. This is largely responsible for the reputation Hitler has been given for brutality and even “war crimes.” Unfortunately, his own generals were sometimes unwilling to carry out these orders, causing greater difficulties and losses for German soldiers. Parts of the book are about these conflicts and disagreements which led to assassination attempts against the Fuehrer hatched by a faction within the Army. Four chapters out of thirteen describe in detail the extent and ramifications of the Valkyrie plot of 1944. Giesler wrote of these officers:

“[T]hey were still entrenched in the 19th century. They hadn’t learned anything at all. They hadn’t recognized that this is a war of life or death, not restricted to soldiers, folk or the nation. […] a fateful struggle in a revolutionary fight for the existence of Europe—in a battle for a new idea of life.” (p. 190)

The prophetic sense of a fateful struggle for Europe was exactly right, considering how Europe is being destroyed in our present century by the replacement of our race with huge flows of migrants from the Third World. This is what happens when international concerns take the place of national concerns.

After the two massive firestorm-and-phosphorous bombing raids on Dresden on the night of February 13, 1945, very late that night Hitler said in Giesler’s company:

“What was possible after the terror attack at Hamburg, Cologne, Berlin and wherever else—to trace the victims—at Dresden is impossible. […] I think back to the situation in 1940. The defeated French and English forces were encircled at Dunkirk. At that time I was pondering, realistic and responsible, as a soldier (1st WW) and politician. Should I admit that an ethical thought might have been involved in my deliberating? It is not easy to order the annihilation of hundreds of thousands.

Today, my decision is considered a mistake, stupidity or weakness. Naturally, after the years of armed clashes degenerating into actions of terrible destruction—today, after Dresden, I would react differently.

During the lucky, but also during the hard, unlucky battles of those war years, I tried to be sensible. I made the effort to hold on to some kind of humanity—if one could react that way responsibly in the middle of a relentless war. I did not lead a war of destruction against cities and cultural institutions, neither when occupying a place nor moving out—Rome, Florence or Paris. They should not pretend keeping Paris undamaged was the merit of the resistance or even the Allied forces. If I would have thought the defense of the city would have been necessary, that would have happened. And if I wanted the destruction of Paris, a battle-experienced commander with a division would have been enough.” (pp. 228f.)

There are numerous examples of Hitler’s thoughtfulness, his acts of friendship and kindness. One is on page 13, when after viewing the crypt of Napoleon in the Dome des Invalides in Paris, Hitler orders Bormann to see that the body of Napoleon’s son by the Austrian princess Maria Luisa, buried in the Habsburg royal tomb in Vienna, is removed to his father’s crypt in Paris, as a gift to the French people.

In October 1940, Giesler meets Hitler for lunch at a Munich restaurant as the latter is en route from Spain to Italy. The subject of Rudolf Hess comes up and Hitler confides that the is worried about Hess’s hypochondria and state of mind, not only because of Hess’ high position but because he is sincerely fond of him.

“That I keep him in such high esteem, that I feel an obligation, well, he is the ‘Faithful’ since the beginning of the National Socialist struggle.” (p. 76)

On one visit to Winniza in 1942, Hitler said to him after lunch.:

“Giesler, you are not only exhausted but you also have not had enough sleep. I can see it. You will now take a walk – naturally with company – and then go to the sauna and you will sleep well. I’m very busy with military discussions and deadlines; no planning talks today. I’ll see you at tea-time, late evening after the Lage.” (p. 52)

Hitler always defended Martin Bormann from the criticism he received for shielding the ‘Chief’ from so many who wanted appointments with him. On one occasion, Giesler quotes Hitler as saying, “Please go along with Bormann” and “He relieves me, he is steady, unshakable and an achiever—I can depend on him.” Another time, Hitler told Giesler:

“If you want to drive away from here early, mad because of Bormann—but you are Mrs. Bormann’s guest, and you are also my guest—no, you cannot do that to us. By the way, let it be said to you, in that case Bormann acted absolutely correctly. He naturally should have given you some explanation, which I herewith do now …”

Giesler writes:

“In restrospect, I always found out on my own that Bormann was correct to get tough on me, or that he acted on Hitler’s order.” (pp. 142f.)

When Giesler was staying in the Fuehrerbunker in Berlin in February 1945, he got a call from his brother telling him his mother had been killed by the guns of an American bomber in Munich. When he went to give word to Hitler that he was leaving, Hitler walked out of the military meeting to greet him and give his condolences. Then the Fuehrer told him he would not allow him to travel alone, took him into the meeting room until it was finished, then walked with him back to the bunker, telling him that Kaltenbrunner, the Reich security chief, would take him to Munich in his own train, as he was going there that night. When Kaltenbrunner arrived, the two said goodbye.

“Hitler gave his hand and, as so often, he laid his left hand on my arm. Wordlessly, I looked into Hitler’s eyes for the last time.” (pp. 231-233)

Because Hermann Giesler spent a considerable amount of time with Adolf Hitler both alone and in the company of others, in the various Fuehrer military headquarters as well as on trips to cities in connection with architectural work, what he tells us should carry some weight. This book is packed with interesting tidbits about the German Fuehrer, as well as long conversations with him. Often, he is quoted at length. Getting at the truth will come from expanding our sources of information past the usual court historians. A careful reading of this book can be a start of that.

[Online source: http://inconvenienthistory.com/10/2/5462]