Critics of U.S. President Donald Trump’s efforts to halt illegal immigration claim that it is “impossible” to deport millions of illegals currently in America—but ignore the fact that it has been done before.

Officially called “Operation Wetback,” the program, launched in 1954, saw well over two million illegal aliens arrested and deported back to Mexico—all in cooperation with the Mexican government.

The origin of Operation Wetback can be traced to what was called the “Bracero” program, which was a formal agreement between the Mexican and American governments during World War II.

This program allowed Mexican laborers to work in the United States under short-term contracts in exchange for stricter border security and the return of illegal Mexican immigrants to Mexico.

The Bracero program was launched in 1942, and more than two million Mexican nationals took part in it. However, only those Mexican who could show that they were going to specific places of work, had contracts, and could show that they were going back, were allowed in.

The wages that the “Braceros” brought home made the scheme highly popular in Mexico—but had the unwanted result of millions of Mexicans turning their eyes north—even if they did not qualify for the program.

As a result, illegal immigration over the U.S.–Mexican border became a serious problem for the first time. The presence of legal Braceros was often used as a “cover” to hide the presence of illegal immigrants—a fact which finally led to the demise of the Bracero program.

Before its collapse, however, the numbers of illegals in the U.S. had reached, by some estimates, several million. The government decided that something had to be done—and quickly.

In 1953, U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) Commissioner Argyle Mackey, writing in the official INS journal, said that the “human tide of wetbacks” was the “most serious enforcement problem of the Service.”

“Reports of good work in the States,” Mackey wrote, had turned the Mexican “trickle into a flood,” and that for “every agricultural laborer admitted legally, four aliens were apprehended.”

Willard Kelly, the assistant commissioner of the border patrol, called it “the greatest peacetime invasion ever complacently suffered by any country.”

Finally, the Mexican government made a plea to the U.S. to help stop the illegal entry of Mexicans into America, because it was depriving Mexico of much-needed laborers to build their own economy.

The growing problem led to the creation of Operation Wetback.

President Dwight Eisenhower appointed General Joseph Swing—who had won fame commanding the 11th Airborne Division during the campaign to liberate the Philippines in World War II—to plan the operation.

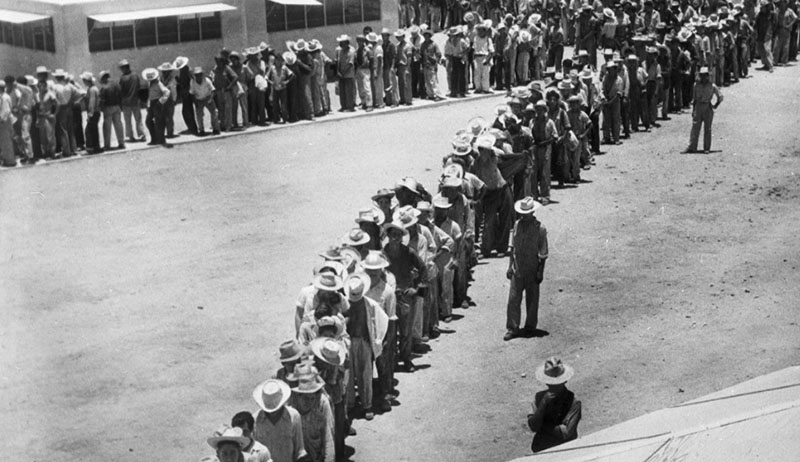

After five months of preparation, the program was officially launched in May 1954, when teams of Border Patrol agents, buses, planes, and temporary processing stations began locating, processing, and deporting Mexicans who had illegally entered the United States.

The main focus areas of the operation were the cities of Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago, and the target border areas were in Texas and California.

Those deported were handed over to Mexican officials, who in turn moved them into central Mexico, where there were many labor opportunities.

The operation was a huge success. In the first twelve months, at least 1,078,168 illegal aliens were arrested and deported.

The following year, the number of apprehensions declined to 242,608, and further drops were recorded each following year for the next eight years.

These figures did not include the “self-deportations” which always accompany such an operation—that is, the number of illegals who leave by themselves rather than waiting to be apprehended. These “self-deportations” numbered over half a million from Texas alone.

Beginning from the Rio Grande Valley, Operation Wetback spread quickly; on the first day, July 15, 4,800 illegal immigrants were detained and deported, and every day after that another 1,100 illegal immigrants were sent back.

The first set of deportees were repatriated through Presidio because the Mexican city across the border, Ojinaga, had rail connections to the interior of Mexico by which workers could be quickly moved on to Durango.

A major concern of the operation was to discourage re-entry by moving the illegals far into the interior of Mexico, thereby making it onerous for them to return.

As the pace of deportations picked up, the illegals were transported across the border on trucks, buses, and finally even by sea.

Illegals were ferried from Port Isabel, Texas, to Veracruz, on a large number of ships employed for the purpose—and this quickly became a favored method of deportation because they carried the Mexicans farther away from the border than did buses, trucks, or trains.

Significantly, the forces used by the government were small, numbering no more than 750 men.

The program was also supported by many U.S. Trade Unions, who correctly saw the mass invasion of illegal immigrants and the resultant lower wages as a threat to American workers.

The Texas State Federation of Labor even produced a study entitled What Price Wetbacks?, which concluded that illegal immigration in United States agriculture damaged the health of the American people, that undocumented migrant workers displaced American workers, that they harmed the retailers of McAllen, and that the open-border policy of the American government posed a threat to the security of the United States.

The success of the operation shows conclusively that it is physically possible to control illegal immigration—and that the only ingredient which is required is the political will to undertake such a venture.